Next of Kin

- Admin

- Sep 20, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Oct 4, 2025

Accounting for the Dead

One of the more enduring popular beliefs is that as the conditions on the Western Front were so grim, in both bottomless mud and the endless artillery barrages, that all the men simply disappeared. They were absorbed into the morass and been consumed by the man-eating monster. This idea is prevalent in the poetry and literature that the war somehow needed to be fed with the lives of the poor bloody infantry. The idea that a man or men could simply just disappear and that the army would make no attempt to account for them is not credible. The army, despite the accusations of how good or bad they were at fighting, knew how to count and they had created returns and lists for everything. In addition, roll calls were regularly held as the men had to be paid, fed, equipped, and sent on leave. One of the critical parts of the accounting process was that of recording the dead, simply because the army did not like paying for soldiers who no longer had a usefulness and the army liked to know who was alive and who was dead. The bodies of the dead, if the body existed, in some cases the body simply consisted of various parts, were buried as quickly as possible. Bodies were unidentifiable because their identity tags were missing, blown to bits or, in the case of battlefield burials during an action, simply no time to look for any form of identity. The problem of recovering, identifying and burying the dead was apparent from the beginning of the war. As the fighting went back and forth the dead often lay around and many could not be recovered with many more buried only for their grave to be churned over by the artillery fire their bodies to join the thousands of the missing.

Falkirk District man Second Lieutenant Eric Jamieson, 11th Battalion Argyle & Sutherland Highlanders. Eric was leading his men in action north of the Ypres-Roulers Railway on 22 August 1917 when he was posted as missing, it was recorded in the War Diary and his family informed. His death was confirmed in April 1918. In October 1920 his body was found in an unmarked grave on the old battlefield and exhumed and reburied at Dochy Farm New British Cemetery. He had been identified from his identity disc, badge, and pince-nez glasses.

Graves Registration Commission

Graves and cemeteries sprang up in a random fashion and the recording of the dead by the various units was on an ad hoc basis. It was the work of a British Red Cross unit, sent to France in 1914, under the leadership of Fabian Ware that was to be the catalyst for the founding of the Imperial War Graves Commission. Ware arrived at Lille in northern France in September 1914 to take command of a group made up of private cars and drivers that made up the Red Cross ‘flying unit’ The group was ‘made up of middle-aged and young alike’ and had been operating in the British sector treating the wounded and even venturing into German held territory to rescue prisoners of war. Searching for the wounded was their chief role, but they also ‘began to collect evidence about the British dead, noting down who they were and where they had been buried.’ This was not unusual as the British Red Cross had kept in touch with their German counterparts via Geneva and shared information on the missing men and whether they had been taken prisoner. During October 1914 the unit received a visit from Dr Stewart a Red Cross Medical Assessor. This visit proved to be an important one in the development of the unit into a Graves Registration Unit (GRU). It was Dr Stewart who committed the Red Cross to paying for durable inscriptions for the crosses and for providing the means to enable Ware’s unit to mark and register all the British graves it could locate. All through the winter of 1914 and into the spring of 1915 the search for graves went on. By 1916 the GRU had become a part of the army and had been renamed the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries (DGR&E). Each Field Army had a Deputy Assistant DRG&E. Grave registration in the field fell squarely on the shoulders of the unit Chaplains. They were responsible for filling out the proper form (AF W3314) that included the information about the grave, and forwarding to both the DADGR&E and the DAGGHQ 3rd Echelon. Information submitted included map references using the 1/40000 or 1/20000 trench maps, or detail descriptions of localities on the back of the form, in addition to the usually expected basics such as the man’s name, unit etc. He was also responsible for the marking of the

graves. However, many dead were interred into already authorised cemeteries. In this case special instructions were issued as each authorized cemetery was usually under the care of a Graves Registration Unit. The actual interment of graves was up to the unit. The term “unit” could mean many things; internment by the unit of the actual casualty, internment by Casualty Clearing Stations, Field Ambulances, General Hospitals, Graves Registration Units etc. Grave registration units were non-permanent units, that is some lucky unit was detailed to perform that task and it could be any one. Basically graves registration was the responsibility of the unit responsible for the casualty or the unit finding the casualty. The bodies were interred in graves five feet deep, two feet wide, six feet six inches long, and not more than one foot apart. There was to be a path not more than three feet wide between the rows. A chaplain was to oversee the burial.

Gunner William McAlonan, 81st Battery, 5th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, was killed in action on 20 March 1916. The Battery was attached to the Canadian 3rd Division and were providing fire support at St Eloi. His gun was hit and he was killed along with five of the gun crew. His burial was reported by the Reverend A G Wilken attached to the Canadian 8th Infantry Brigade. His burial place was also recorded by the Graves Registration Unit.

Identity

At the beginning of the war every soldier wore one red identity disc and this was removed, along with his pay book and handed in, as proof of his death. From September 1916, and following an Army Council Instruction, two identity discs, the existing red one and a new green disc that was eight sided were issued to every soldier. The idea was that the red disc would be removed as before and the green disc would remain with the body. Both discs were marked with the man’s surname and initials, his regiment, service number, and religion this was usually in the form of METH for Methodist or CE for church of England. The man wore the tags together round his neck and they were made of a biodegradable material which was a major flaw. The men took to purchasing bracelets with their details inscribed or to marking equipment with their name and service number. Falkirk District man Private James McCarrol, 'C' Company, 2nd Battalion Royal Scots. In October 1924. James McCarrol’s body was found in an unmarked grave west of Sanctuary Wood. He was identified by his Gas Helmet bag which was inscribed with his service number and initials, ‘2272 J.M.C.' His body was reburied at Railway Dugouts Burial Ground (Transport Farm).

He died instantaneously and suffered no pain

This is a very popular form of death! It can be seen in the many letters written by the friends of the dead to the dead man’s next of kin or from their Company commanding officer. These letters were done to console the bereaved and to reassure them that they did not suffer in death. Nonetheless, these letters did contain some graphic accounts of the action and the not so instantaneous death. Falkirk District man Private William Easton, 17th Battalion, (Rosebery) Royal Scots, was killed while carrying his Colonel on a stretcher. He is buried at Nine Elms British Cemetery. The battalion chaplain wrote to William's wife that: ‘You will probably have heard by now of your husband’s death… Our Colonel was wounded and your husband was carrying him in a stretcher along with another soldier, when a shell came over and killed all three…’ The Company commander of Private James King, 1st Battalion Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders, wrote to the parents of James that: ‘… he died as you would have him die, with his face to the enemy, upholding the traditions of our dear country and the famous regiment that now mourns his loss… It is a loss that can never be replaced.’ Lance Corporal Michael McGowan, 'B' Company, 8th Battalion Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. In a letter to his parents his Company commander wrote that: ‘… he died instantaneously and suffered no pain may be some help to you in your great sorrow.’ Private Robert Rae, 2nd Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders was killed in action on 21 October 1914 in the fighting around around Mesnil. He is listed on the (Royal) Berkshire Corner Memorial at Ploegsteert. He was one of four sons as well as Robert his brother Alexander was also killed on 31 December 1915 and is buried in Cambrin Churchyard Extension Cemetery. Another brother, Adam, was serving in the 2nd Battalion and was seriously wounded in 1916, and the fourth brother John was serving as a Driver in the Army Service Corps. It was Adam who wrote to his parents concerning Robert’s death ‘I am very sorry to break the news about Robert. He was killed on the 21 October, being shot through the heart, as I was told by the Sergeant-Major. He was reported killed by the men who lay next to him, but you will get it through the War Office. It will be a very hard blow to you, but duty is duty.’ He seems to hold out some hope to his parent; ‘It is just possible that he might have been captured by the Germans, but one of the officers also reported him killed.’ He concluded his letter: ‘May God spare us all and give us a safe return.’ L/Cpl James Cameron, 2nd/6th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment, was killed in action on 3 September 1917 at Pommern Redoubt on Frezenberg Ridge. In a letter to his parents a comrade wrote that they were going over and encountered heavy machine gun fire: ‘Jimmie was leading his section, and he turned round and said, ‘Come on boys, let’s get at them.’ The Regiments chaplain wrote to his parents that they were taking a German strong point when an explosive bullet struck Lance Corporal Cameron in the back and killed him instantaneously. Private James Crane Burnside, ‘D’ Company, 1st Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, was killed in action on 10 May 1915 during the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge. In a letter to the parents of James Burnside Lance Corporal J Combe captures some of the desperation of the fighting: ‘I am sorry to convey sad news of your son, who was killed in action on 10 May. We were shelled out of our trench, and had to leave under a heavy fire. Shortly before we left, your son did splendid work in dressing the wounded, as we had a great many casualties.' In a subsequent letter he wrote that James and a comrade had been buried in a wood on a hillside (probably Railway Wood) his body being lost in the fighting and he added: ‘his death was instantaneous, as he was struck by a piece of shell about the face and body. We had been shelled out of our trench and it was in the retirement that your son was killed.’ L/Cpl Combe was recommended for a Distinguished Conduct Medal for carrying despatches. Private John McDonald, 1/6th Battalion Black Watch, was killed in action when his Battalion was employed in providing working parties for the Royal Engineers and were billeted in the Canal Bank dugouts at the Yser Canal. His mother received letters from both the Battalion Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel T M Booth and the Battalion chaplain. They both expressed their sympathy at her loss and gave details of how her son was killed. He died with fourteen others when a shell destroyed their dug out. The letter from Lt Col Booth states that her son was buried in a military cemetery with a burial party carrying him to his grave and a piper played a lament after the service. He also advised that he was arranging for a cross to be placed to mark her son’s grave. He is buried at Vlamertinghe New Military Cemetery L/Cpl David Lomond, 11th Battalion Royal Scots, was killed in action on 29 April 1916 at Le Gheer, Ploegsteert. For his part in defending a trench during the Battle of Loos in 1915, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. When he was home on leave the village organised a celebration to recognise his heroism and the honour it had brought to the district. At the well-attended meeting he received a large amount of gifts from the community. The meeting was presided over by the local minister Reverend J R Garvie who said that: ‘.. Private Lamond had brought fame and glory to the district, and carved out for himself a niche in the temple of fame.’ He was killed by a sniper with the Falkirk Herald reporting his death

Case of an Alias

There were many men who sought anonymity for various reasons and served under an alias. Private Robert Edward Sanders (served under the name of Maurice Dane) was from Kentish Town in London. While employed as Second Mate on the ship ‘Mount Stewart’ he deserted the ship at Port Victoria and enlisted on 27 March 1916 in Adelaide under the name of Robert Edward Sanders and listed his employment as a Labourer. His two brothers had enlisted in the British forces, one was a prisoner in Germany. His mother, a widow, wrote to the Australian authorities, via a solicitor, in September 1917 advising them of his real name and that she was his Next of Kin and that she was seeking a pension. A witness statement, from an Australian friends of Maurice, as to his true identity was also provided. He is buried in Bethleem East Cemetery, Grave Special Memorial 1.

Searching for Answers

Relatives who were grieving and seeking more information would write to the War Office or place adverts in the local paper for news of their fate. Private William Melville ‘Y’ Company, 12th Platoon, 17th Battalion (Rosebery) Royal Scots, the Battalion was a Bantam Battalion. The first Bantam battalions began to appear in November 1914, one of which was the 17th Battalion, Royal Scots which was also one of the seven ’Pals’ Battalions recruited in Scotland. William was killed in action on 30 September and is buried in Zantvoorde Military Cemetery. William's wife received a letter from the Battalion Chaplain informing her of her husband's death. The pain and anguish of her loss is evident in the letter she wrote to the Army asking for more information concerning the circumstances of her husband's death.

Private James Peebles, ‘F’ Company, Scots Guards, was killed in action on 24 October 1914 during the desperate fighting at Reutel Ridge near Polygon Wood. His family had not heard from James and the War Office had posted him as missing. His wife had been enquiring through the Falkirk Herald in the hope that a relative of a comrade had heard of his fate. She received a postcard from a Private J Tattersall, a PoW at Gottingen near Hanover, in which he wrote that he had seen her notice and that he was sorry to tell her that his chum, J Peebles, was dead. He wrote to the wife of James Peebles on the 30 June 1915, stating that: ’Dear Friends I received your letter and I am very sorry at the news which I have got to give you. Your son James was killed on the 24th October at six am near YPRES. I can tell you his death was painless as he was shot through the brain and never spoke. I straightened him out in Trenches. I was wounded then (he was shot in the hand) and got captured at 6.30am and brought here. Your son was one of the best soldiers and never grumbled as we got it very hard.’ He said that the Germans had taken James's number disc, his belongings, and some photographs and other things from his body.

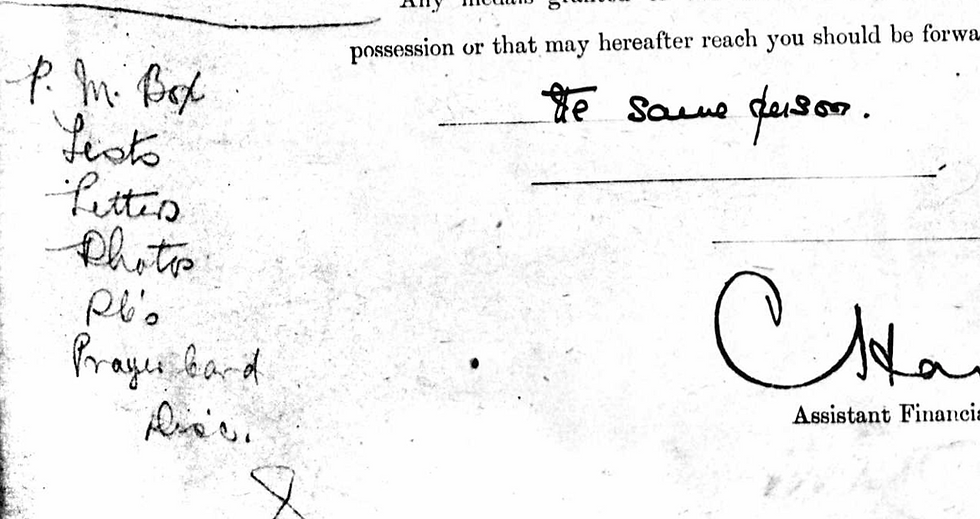

Personal Effects Returned to Relatives

In general personal items were passed on with a statement of what had been found and removed from the body. The inventory could be long or short for both officers and other ranks. Australian Captain William Thomas Bryan, serving with the 44th Battalion, 11th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Australian Infantry Division, was killed in action on 8 June 1917 at Messines. He is buried in Bethleem East Cemetery, Grave A.2. His burial was presided over by the Reverend A.A. Mills. William’s wife Beatrice sent a telegram to the Base in Perth about her husband’s welfare after she had heard rumours that the Battalion had been in action. On 16 June 1922 she received a letter from the Base in Perth that included her husband’s damaged and degraded fountain pen and some medallions taken from his body by the grave exhumation party. The mother of Private Archibald Marr, 1st Battalion Royal Scots, killed in action on 12 May 1915 at Zouave Wood, and from Dennyloanhead in Falkirk District, received her 19 year old son’s effects

A Treasured Picture of their Grave

The Graves Registration Commission (GRC) received many requests to have pictures taken of a relative’s grave. The Army had prohibited any photographs to be taken after the images of British and German troops fraternising during the Christmas Truce of December 1914 had appeared in the press. The GRC were granted special permission and three professional photographers were employed to travel around the Western Front to take photographs. One of these photographers was Ivan Bawtree who was seconded by Kodak in London in 1915 to the GRC. In his book ‘Photographing the Fallen’ Jeremy Gordon-Smith records the work of his Uncle Ivan Bawtree. I had the pleasure of taking Jeremy to the various locations in the Ypres Salient that feature in the book. Jeremy recounts in the book how the Bawtree photographs had been saved from destruction. It was in 1974 when David Bawtree a great-nephew of Ivan was visiting him at his home. Ivan took David to the cellar where he had sheltered during the blitz and it was here that David found two cardboard boxes containing some 600 photos printed from the glass negatives and in three albums as well as a number of original prints in

other albums and envelopes. Ivan was unsure about what to do with the photographs, he used to make two copies of each photograph one for himself and one for the GRC records, and had planned to throw them out! David contacted the Imperial War Museum and you can now view the Bawtree Collection copyright Jeremy Gordon-Smith on the IWM site. Ivan records in his diary a visit to photograph Hospital Farm Cemetery and an incident with a Military Policeman who didn’t like the cameras: ‘This was a kind of rest camp. the men all lived in dug-outs which looked very comfortable but I shouldn’t care to be in them in wet weather. There was a nice little cemetery in a field here and we finished it. On the way out the M.P. at the gate stopped us and asked what we were doing with cameras. We straightaway showed him our passes (both kinds) but he tried to be nasty even then, though with no success.’ The work of the Graves Registration Unit was described by one of Ivan’s colleagues Corporal Reginald Bryan and recounted in Jeremy’s book: ‘It was really melancholy work, and a rather sad task, but it was a necessary one, as apart from its sentimental value, it was necessary from a sanitary point of view. However, we didn’t go about with long faces but tried to keep as cheerful and jolly as we could.’ (Source: Photographing the Fallen, Jeremy Gordon-Smith)

A Soldier’s Grave

Then in the lull of midnight, gentle arms

Lifted him slowly down the slopes of death

Lest he should hear again the mad alarms

Of battle, dying moans, and painful breath.

And where the earth was soft for flowers we made

A grave for him that he might better rest.

So, Spring shall come and leave it sweet arrayed,

And there the lark shall turn her dewy nest.

Comments