St Eloi Mine

- Admin

- Apr 6, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2025

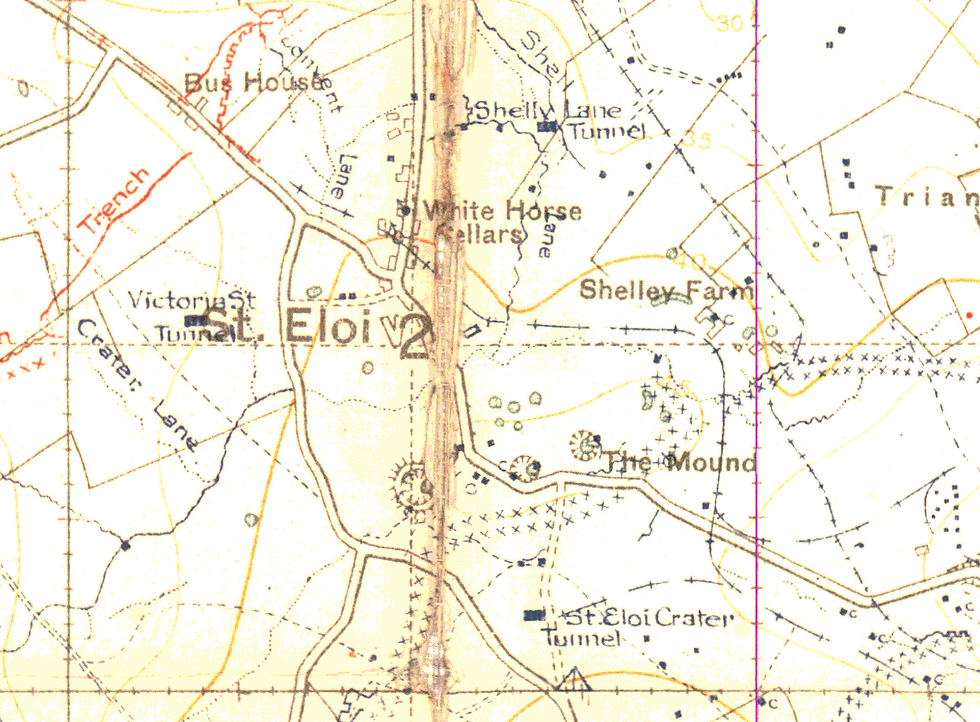

This area was a mining hot spot with each side blowing mines and countermines. The front line ran through the houses of the village. By the end of 1915, 33 mines and 31 camouflets had been blown by both sides around The Mound, the high ground that stood to the north of the village, and was formed by the spoil from the old brickworks, and was ten metres high and 100 metres across.

Today, the ground around St Eloi still has evidence of the mining activity in the area. The 1915 craters have been filled in with housing built over them or have been ploughed over. The larger, 1916 craters, are still visible. By the N336 you can see craters 4 and 5 now filled with water, they were blown on 27 March 1916. On the angle of the roads N336 and N365, behind the houses and accessed through a gate, the security code can be obtained from the Ieper Tourist Office, is the June 1917 mine.

Queen Victoria Shaft

In August 1916, 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company, commanded by Major Cy North, took over the area from 172 Tunnelling Company and started work on a deep shaft in the British lines at Bus House. The shaft was sunk to a depth of 30 metres (100 feet) and was named by the Canadians ‘Queen Victoria’.

At nine metres down (30 feet) the tunnellers created a station and a chamber to house a power plant which was installed in October. The main drive went forward with slow progress due to the hard clay but they soon picked up and reused the gallery created by 171 TC which they had created for their mine one year earlier. This gallery which had been flooded was drained out and cleaned up and the gallery was driven beyond No’s 2 and 3 craters, from the earlier mining in 1916. By May 1917, the gallery had been driven 503 metres (1,650 feet). The tunnelling section under the command of Section Officer Captain Stuart Thorne now created the chamber and laid the largest British charge of the war a staggering 95,300lbs of ammonal plus 300lbs of gelignite and at a depth of 38 metres (125 feet). The Germans had laid a larger mine, by 5,500kg, at Vauquois in May 1916.

The Mine is Laid

The Canadians finished laying the charge on 28 May 1917, nine days before zero. They started a second drive towards craters 4 and 5 however, this was abandoned due to a lack of time. Three firing circuits were put in place each with ten detonators connected in a series with each detonator placed in a stick of gelignite with twelve other sticks secured to it. These were then embedded into a 50lb tin of ammonal. Each circuit had an individual exploder. The firing party was to stand in a convenient standard dugout, or more probably in an open trench in the rear as the dugouts had been cleared. One plunger was to be pressed by a young electrical engineer from Winnipeg, Lieutenant Richard O’Reilly; the other by Captain Stuart Thorne.

Germans False Sense of Security

The Germans felt secure at St Eloi as they considered this to be one of their most successful defensive mining systems. They had drained the earlier craters and consolidated them and also gone down to a depth of 30 metres (100 feet) and in places had gone to a depth of 40 metres (138 feet) and had galleries under the British positions. The Inspector of Mines for the German Fourth Army, Lt Col Otto Füsslein, had likened the German countermine defences as like a torpedo net around a battleship. However, they had not been able to sink shafts beyond the crater area and the Canadians had simply gone round the German defensive system. German over confidence was also reinforced by information they had received from prisoners which suggested to the Germans that their counter mining had destroyed the British mining in the area. What the Germans did not realise was that the British had already driven their deep mines before the Germans had themselves gone deep.

Tunnellers Memorial

This memorial commemorates the March/April 1916 actions around the mine craters blown on the 27th March and the units mentioned on the memorial are the 172nd Tunnelling Company, 3rd Division, the 2nd Canadian Division and the 7th Belgian Field Artillery.

Comments