PART ONE: Development of Shelters, Dugouts and Bunkers in the Ypres Salient

- Admin

- Dec 4, 2022

- 13 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2025

Shelters, Dugouts and Bunkers in the Ypres Salient: An Introduction

In Part One is a short history of the development and innovation of concrete bunkers, shelters, and pill boxes in the Ypres Salient. Many of these structures – some showing signs of damage – still exist and can be visited today. Parts Two and Three cover the development of German and British shelters and bunkers in more detail.

Introduction

The British Army Royal Engineers went to war in 1914 ill prepared for the siege warfare that was to develop. Their training was in temporary defences around mobile warfare and the Manual of Field Engineering which had been published in 1911 and subsequently reprinted in 1914 was done so to cope with the expansion of the Army. The manual gave advice on cover for observation posts, artillery, and machine guns, and it was all based on overhead cover as protection against shell splinters. However, the British, by 1918, had overtaken the other belligerent nations and had developed systems and standard designs for bunkers both pre-cast in place and pre-cast concrete.

The French, like the Germans, had been updating their frontier forts and defences since the 18th Century and both had fortification and siege engineers in their armies. From the beginning of the war both the French and the Germans had sufficient expertise to deal with what became a static war and the defences required including shell-proof shelters for their machine guns, artillery, command posts and aid posts. The term ‘bunker’ a commonly used word today and used to describe the storage place for fuel or coal, was not used by either side in the First World War. The word appears to have originated with the Germans who began to use it to describe their constructions in the 1930s. The word ‘pillbox’ was first used in the war diary of the 63rd Field Company RE, which was attached to the 9th (Scottish) Division, when they used the term Pillar Box in their work schedule for March 1916 when at Ploegsteert Wood recording: ‘Royal Artillery Observation Posts and MG emplacements, ‘Pillar Boxes’ sites selected.’

The name 'Pill Box' also did not originate from the medical container used to store pills as this was round whereas the concrete pillbox encountered was square or rectangle.

The Times newspaper, in their report describing the opening attack of Third Ypres on 31 July that featured in the newspaper on 2 August 1917, used in their report ‘… the German pill-box…’ to describe the concrete shelters. The British officers, in their reports in the battalion war diaries, described German defences as ‘concrete blockhouses’ or ‘concrete dugouts’ and not Pill Boxes. The term was in regular use by the end of 1917 and featured in war diaries although blockhouses and shelters continued to be used.

The Salient was an active Battle Zone

From a British perspective, the fighting in the Salient has always appeared as a permanent feature from First Ypres in 1914, to Second Ypres in the spring of 1915, and the fighting around Mount Sorrel in June 1916, to Third Ypres in the summer of 1917, the German spring offensive in 1918, and the advance to victory in September 1918. In truth, it was relatively quiet between June 1916 to June 1917 however, the spectre of being fired at from three sides brought its own horror to the British troops. For the Germans, their High Command had decided early on that the Flanders sector should not be an area that involved major attack, that said, Second Ypres was an attack that we are still trying to understand what the strategic objectives were to have been. The Germans also knew that the Salient would be a focus of British strategic planning and therefore, began, from late 1915 to the end of 1917, the ‘bunker’ phase in their defence development and to build a sophisticated defensive system that could adapt to the offensive weapons in particular, the weight and accuracy of the British artillery.

The Geology

In Flanders, just below the surface soil, which is a layer about one metre thick, is a layer of sandy loam, with underneath this, a layer of blue clay. The sandy loam has a limited permeability, the blue clay, known as Ypresian, today it has a less historically emotive description of Kortrijk Formation, in Britain it is known as London Clay. This is a marine geological formation, and it is virtually impermeable and shrinks when it is dry. It is about one hundred metres thick and hardly any water can penetrate through it. This clay was both a help and a hinderance to the engineers who worked with it and in it. It has a blue grey colour when freshly dug and this changes to a dull brown when it oxidises in the air.

The area is very fertile for farming purposes however, it is also very marshy. The draining of the ground for farming began in the Middle Ages and this saw the digging of ditches and canals however, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that field draining systems were put in place. It was this network of field drains and ditches that were destroyed by the artillery shelling of the First World War and affected the draining of groundwater and rainwater. It was also the clay that acted as a barrier to the drainage of water into the lower strata and so forming pools and a system of semi-permanent lakes that we see in the photographs. This resulted in the water filled trenches and dugouts that were dug as siege warfare took hold from late 1914 onwards. Gerald Burgoyne, officer commanding ‘D’ Company, 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Rifles, 7th Brigade, 3rd Division, was in the trenches in the Petit Bois area and recorded in his diary on 6 January 1915: ‘On my left the trench is nothing more than a water course, very little head cover, and only some 80 to 100 yards from the Germans in Petit Bois. Parts of my trenches (H2) we cannot even man; a spring runs through it, and the bottom in places is a sort of quicksand into which I have sunk to my knees, and the suction is so great a man cannot get out without help. Sent down some planks to build up the parapet where a man was killed yesterday…’ To overcome this, trenches, on both British and German sides, were partially dug below the surface and mainly above the surface in effect breastworks predominated.

Breastworks

As we have seen, breastworks were a necessity in places of high groundwater. Around Ploegsteert by the spring of 1915 most German trenches were constructed using sandbags to build a wall above the shallow trench. This consisted of a high parapet facing the British with a low parados on their side. Most of the sandbags were not made of the standard hessian fabric we have come to associate with sandbags but with any fabric, and of many colours that was available. Some were made of blue and white linen, mattress ticking, curtain fabric and even from dress clothing. The breastworks were not that strong with the bags being filled on the spot and built up in the style of brick walls with stretcher bonds used to hold them together. They were built to a metre thick to offer protection against bullets and shrapnel. The breastworks were also constantly under attack from the weather with the rain washing out the contents of the bags so weakening the structure and the bags rotting away.

The Topography

The country, with its mixture of villages, hamlets, farmhouses, hedgerows, woodlands, made excellent locations and features for dugouts, bunkers and blockhouses for the German defenders and Allies alike. As well as being low lying, the area of the Salient has a series of low ridges each one slightly higher than the next and these formed a semi-circle to the north, east and south of Ypres. One such in the central part of the Salient, that offered the Germans excellent views over the British lines to the west and south, was the Gheluvelt Plateau. It equally gave good views over the rear area of the German positions. The Plateau, ran from west of Geluveld to Hooge, with Clapham Junction as the highest points, along with the Tower Hamlets Spur. In the north, Pilkem Ridge, a barely perceptible ridge, the Germans had their artillery observation points on this ridge so controlling the front line. Together with Houthulst Forest these ridges were of the utmost importance to the German defensive position in the Salient. In the south of the Salient the Germans occupied the high ground on the Messines Ridge. However, the British also had good observation high ground on Mount Kemmel and Le Rossignol (Hill 63) to the northwest of Ploegsteert Wood. There are many ditches and small streams that cut across the Flanders countryside, and these divert the water to the Yser and Lys rivers. They also form excellent ready-made defensive trenches, if not rather muddy and wet. At Third Ypres the Germans made full use of these ditches and streams that had been destroyed by the shelling and had become wide, almost impassable, swamps. They built their barbed wire defences behind these swamps and had their trenches on the higher ground. To take the German positions, the attacking force had to not only negotiate the swampy ground, the German wire, but also attack up a gently rising slope before engaging the enemy. These were the conditions that the New Zealand Division’s encountered during their attack across the Ravebeek Valley towards the Bellevue Spur near Passchendaele on 12 October 1917. Their casualties, for a few hours of action, were 850 dead.

Development in Trench Construction

A trench is essentially just a slot dug into the ground. The purpose of the trench was to limit the effect of shell blast and to provide protection against bullets and shrapnel. A front-line trench was typically 3 feet 4 inches wide at the top, 7 feet deep and with the sides cut as steep as possible and tapering to 3 feet wide at the bottom. They had a parapet at the front, this was higher to offer protection, and a parados at the back. A raised fire step was incorporated about 18 inches wide at the bottom. The sides were reinforced with corrugated iron, wicker work hurdles, wire netting, timber, or any other convenient material, normally scrounged from neighbouring farms and buildings. From the lessons learnt in the early trench construction, the trench bottoms often had duckboard flooring which aided movement and drainage of water. It was of wooden construction and ladder shaped and were made and stored in the rear areas and brought forward by the support troops. These same principles of trench construction applied in the second and third lines with communication trenches dug to connect the various lines. The communication trenches were wider than the front line and support trenches and this was to allow the easy movement of men, materials, wounded, reliefs, and reinforcements in some safety as they offered some protection against shell and small arms fire. These communication trenches became known to the artillery and were shelled during any form of attack and so, they became less safe. At Hooge the Germans built a supply tunnel under the middle of the Menin Road known as the Hooge Tunnel and it ran as far back as Clapham Junction. What made the trenches of 1916 and 1917 different from those of 1914 and 1915 was not their profile, it was how they were built, or rather their permanence. This was seen in the increasing use of concrete. The Germans built their trenches with the intention of holding the ground and not moving while the Allies saw this form of permanence as defeatist, their intention was to get the German invader off French and Belgian soil, and this could not be achieved by permanence. The British also believed, wrongly, that troops who were in positions that had a feeling of permanence would lose the offensive spirit. The Allied trenches were not defensive but were a jumping off point for the next offensive.

Master of Belhaven and China Wall

Lieutenant-Colonel the Hon. Ralph Gerald Alexander Hamilton. Master of Belhaven was in command of a Royal Field Artillery Battery located near the Lille Gate in 1916. On the 31 January he wrote of the Lille Gate: ‘…The officers’ mess is actually in the Lille Gate, a most curious place. It must be about sixteenth century and was evidently the old guardroom. It is vaulted rooms, or rather three rooms, with no windows, except a few slits, looking out over the moat. The battery is just the other side of the moat. We get to it through a tunnel (the Sally Port) in the ramparts, and across a small wooden footbridge which is known as ‘Pip-squeak Bridge,’ as it is always being shelled by shrapnel.’

On the 9th February, he wrote that he was looking for a new Observation Post (O.P.). His previous O.P. had been the target of German shelling on 4th February with 150 shells landing within 50 yards of the O.P. dugout. ‘This afternoon I took Perry to look for a new O.P. and found two excellent ones: one in Gordon House and the other in the sandbag wall. We had a quick walk down the railway and were not shot at all, for once. The sandbag wall is a great wall of sandbags half a mile long, with traverses every few yards. It reminds one of the Great Wall of China at Shan-hai-kwan!’

German Building Frenzy

The geology played an essential role in the construction of the bunkers and determined the placement of these bunkers, whether they would be hampered by groundwater, and whether the sub-soil could support the structure. From late 1915 to the end of 1917 the Germans embarked on a building frenzy of concrete bunkers and shelters of all kinds. This was in response to the need to bolster the front-line trenches in addition to the second and third lines with shell-proof shelters. These shelters went through repeated design changes to cope with the changing shell calibres that would fall on them. This programme was to be made superfluous by the nature of the war in late 1917, the success of the artillery and mass tank attack at Cambrai had shown that static defences were no match for well-coordinated offensive action.

British overtake others

As for the British, from a standing start in 1914, they had, by 1918, overtaken the other belligerents in standard designs for bunkers. In the Salient, the first recorded British concrete shelter was a machine gun post in August 1915, although the Royal Engineers (RE) of the 2nd Royal Anglesey Regiment, did complete experimental concrete dugouts at Ypres in May 1915. On 1st August 1915, at Wilson’s Farm near St Jan, the 1st London Field Company, RE, later designated 509th Field Company RE, built concrete dugouts for machine gun crews as well as improved the field of fire by thinning hedges.

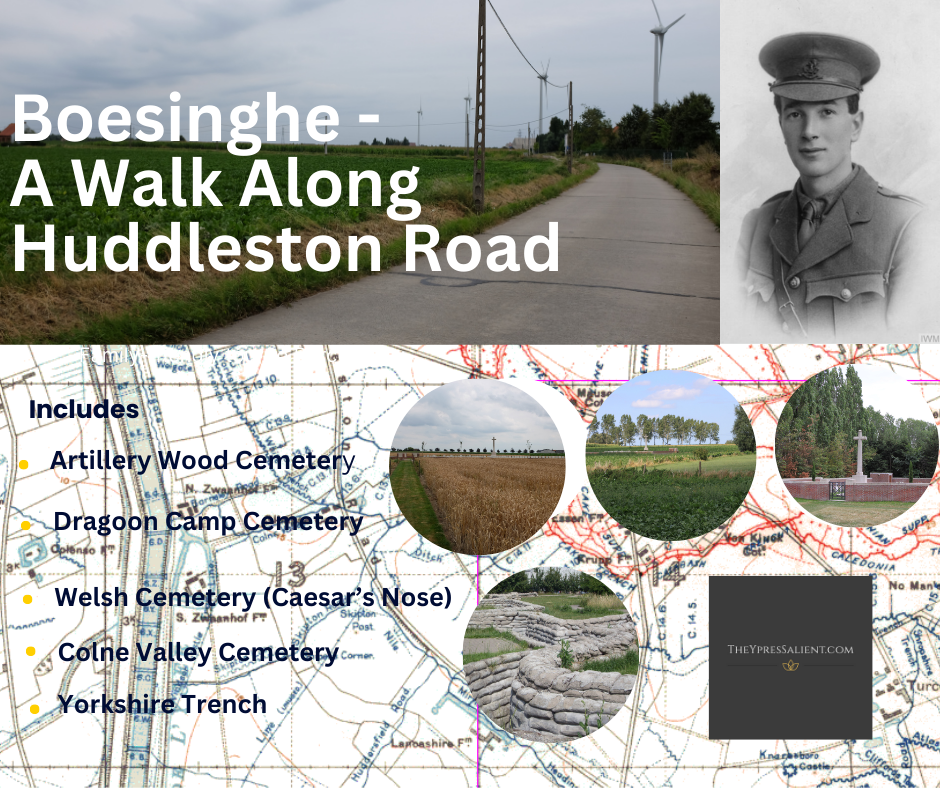

On 14th August 1/2nd West Riding Field Company, RE, they were later designated 57th Field Company RE, built a concrete shelter for a machine gun crew located at Chateau de Trois Tours near Brielen. This is in the wood on private land not accessible to the public. From 1 to 7 February 1916, at Boesinghe, 62nd Field Company was working in ground where the trenches were breastworks due to the ground water. Their War Dairy records the construction of two concrete machine gun emplacements: ‘Two new MG emplacements constructed off Fargate, one north of Wyatt’s Lane, one south of Wellgate. Covered communications trench to each. Each emplacement made about 6’x6’ - heavy frames – two rows of steel girders opposite ways set in concrete. Loophole with girders and concrete above.’

It is worth mentioning that not all the concrete construction work on bunkers was undertaken by the Royal Engineers. The artillery batteries also undertook a lot of work to protect their guns. It should also be noted that much of what we can see today was because of the work of the Commonwealth engineers from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

German Defence Lines

From the winter of 1914/15 the Germans began to develop a defensive line in the Salient. They initially developed defensive lines with a large gap between them this was then developed into an elastic defence and from late 1915 concrete bunkers were added to this elastic defence. Strong points were built, and the bunkers also offered shelter from artillery fire for the troops. With the appointment of von Hindenburg and Ludendorff the Germans revised their defensive strategies. They now adopted a true elastic defensive posture, and they added more depth. A thinly held front line that relied on strong points was combined with counter attacking forces the Eingreifdivisionen. There was a contradiction in this strategy in that they also built a strongly fortified in depth second line some distance from the first. In Flanders this took the form of the four defensive lines, they had planned six, the Albrecht Stellung (position) and Wilhelm Stellung which comprised a network of trenches and dugouts, and Flandern I Stellung and Flandern II Stellung which were bunker lines. It also relied on barbed wire entanglements. Added to this were decoy trenches to mislead aerial reconnaissance. Riegel trenches (switch lines) were incorporated as fortified trenches between the major defensive lines. The Germans could, if they had to, fall back on a defensive line to launch counter attacks and this strategy played a significant part during Third Ypres in 1917. The German defence lines included many buildings, converted to strong points their roofs repaired to deceive British reconnaissance aircraft. The bunkers built in the open were disguised to look like houses with painted windows and doors and roofs added. The British relied more on dugouts of different depths, mainly because they believed that their positions were of a temporary nature and would always be looking to recapture lost territory. The building of these defence lines took a great deal of time and labour. The Germans employed unarmed conscripts, Armierungstruppen, generally made up of men unfit for front line service. The British equivalent was the Labour Corps. The Germans also used Belgian forced labour; it is estimated that over 100,00 were forced to work on the defences. POWs were also used in the construction of the defences with the Russian, Italian and Allied POWs employed from 1915 to 1918.

The construction work also required a massive amount of building material including timber, iron, cement, and sandbags. The Germans recycled old timber beams and other materials. The building materials were transported on a network of railways of various networks and included the use of the Ypres to Menen Tramway. The materials were transported to the dumps and storage areas, one of many was at Veldhoek, and then transported via roads, tracks, or narrow-gauge railway to the front line.

British Development Begins

The British began, after Third Battle of Ypres, to develop a defence in depth strategy themselves in the Ypres Salient and started to build bunkers to consolidate the ground gained. This in the knowledge that a German counter offensive in the Spring of 1918 was inevitable following Russia’s withdrawal from the war. Part Two and Three cover the the German and British shelter and bunker developments in more detail.

Comments